Connemara and the Last Pool of Darkness

Seeking the Fair Land

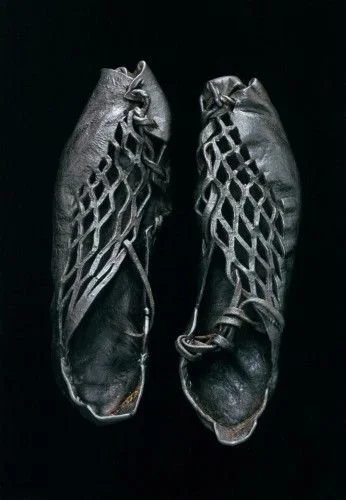

I came across an image a few years ago that has stayed with me: a pair of Iron Age shoes, found in a Danish bog and dating from around 400 BC (National Geographic). They carry the quiet weight of long journeys on foot — the wear of distance, the patience of endurance, the stories such journeys hold.

They always remind me of a book I read as a teenager, Seek the Fair Land by Walter Macken.

The novel opens with a scene of cold, tension, and imminent violence:

The moon shone fitfully through the clouds. It was piercing cold. The waters of the Boyne carried slabs of ice towards the sea…

The men moved cautiously through the orchard, putting each canvas-covered foot carefully on the frozen ground, their weapons gripped tightly in their hands, almost five hundred little white clouds rising from their mouths each time they breathed…

The novel is the first in a trilogy set in seventeenth-century Ireland. It begins in 1641 with Cromwell’s campaign and the invasion of Drogheda. A family escapes by the river at nightfall and travels west on foot toward the mountains of Connemara. The story follows that journey across forests, bogs, and wild landscapes, evading capture as they go. At its heart, it is an account of movement through land — slow, dangerous, and intimate.

That sense of the west as refuge has deep historical roots. Oliver Cromwell’s phrase “to hell or to Connacht” was not rhetorical flourish but policy: the forced transplantation of Catholic families in the mid 17th Century, from the fertile east to the harsher lands west of the Shannon. It was a brutally violent campaign of land confiscation and forced displacement that left its scars for centuries. Connacht — and especially Connemara — became a place of exile. What was intended as punishment also became protection.

Refuge and Home

I grew up in South Connemara, an Irish-speaking region on the Atlantic coast of Ireland, at the foot of a mountain. For me, the idea of finding safety not in walls or towns but in wildness itself — in mountains, bogs, and remoteness — has always felt instinctive. The land becomes both refuge and home.

Connemara, as a region, resists easy summary. It is not merely a landscape of mountains, bogs, and Atlantic light, but a place where geology, language, memory, and imagination are tightly interwoven. To move through it is to travel through visible space and invisible time at once, where every field, stone, and inlet carries layered meaning.

The western edge of Ireland has often been described as wild or empty, but Connemara undermines both ideas. Its apparent sparseness conceals a long record of human presence: ruined villages, field walls, holy wells, coastal paths. The land may look austere, yet it has been continuously read, worked, named, and remembered.

The Last Pool of Darkness

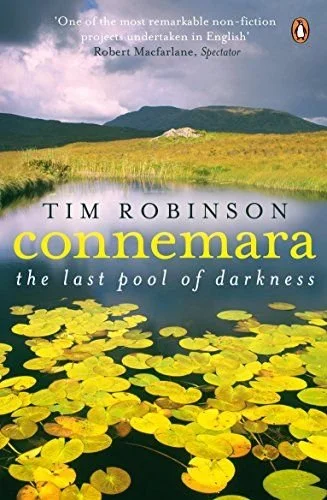

No modern writer captured this complexity more fully than Tim Robinson (1935-2020). Through walking, mapping, and writing, he approached Connemara as a patient listener rather than a romantic outsider. He treated the landscape as a text that demanded attentiveness rather than generalisation.

Robinson emphasised that place is made of stories as much as stone. Townland names, he wrote, are vessels of accumulated meaning, shaped by language, labour, and loss. To know Connemara was to engage with its Irish names — to learn how the land communicates, and how to listen.

This attentiveness deepens in Robinson’s late work, The Last Pool of Darkness, where Connemara becomes a site of reflection on mortality, memory, and disappearance. The “last pool of darkness” is both literal and metaphorical: a place where understanding fades, and certainty loosens.

The phrase often attributed to Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein during his time in Connemara in 1948 — “I can only think clearly in the dark, and in Connemara I have found one of the last pools of darkness in Europe” — captures something essential about the region. Its isolation allows for a kind of thought that depends on silence and obscurity, rather than illumination.

This often-photographed house in Screeb, Connemara, is about ten miles from where I grew up. Because the walk home was long, my grandfather occasionally stayed here while working on the construction of the road.

A Landscape shaped by Presence and Absence

The land itself seems to echo this idea. Bogs swallow paths. Weather erases horizons. The sea redraws the coastline. Even familiar routes change with light and season, reminding the observer that certainty is temporary and attention must be renewed.

Language plays a crucial role in this negotiation with place. Gaeilge survives in Connemara not only as speech but as a way of seeing. Irish place-names describe slopes, currents, textures, and uses that English translations often flatten or miss.

Ultimately, Connemara emerges as a landscape shaped by presence and absence — by endurance, loss, and continuity. Through writers like Robinson and Macken, it becomes not a finished picture but an ongoing conversation, one that does not end in clarity, but in depth.

My mind wanders back to the image of the Iron Age shoes, found in a bog — another pool of darkness — but this time in Denmark. Who knows the stories they carry, or the paths they walked? Who knows what my own ancestors were doing when these shoes were last worn. The land received them there for centuries, a patient witness to the human story.